What Happened to Pilot Season? How Television Used to Manage Risk

For a long time, pilot season television defined how TV shows were developed, tested, and approved. The industry followed a predictable rhythm, with networks using pilots to balance creativity, business, and risk.

At the center of that system was pilot season.

Today, pilot season is often described as a relic from another era. But understanding how it worked—and why it existed—helps explain why television looks and operates so differently now.

What Pilot Season Television Was

Pilot season traditionally ran from January through April and revolved almost entirely around the broadcast networks. During that time, networks commissioned dozens of pilot episodes, which were test versions of potential television series.

The term “pilot” comes from its meaning as a prototype or test run, similar to a pilot project in engineering or aviation. These episodes weren’t meant to be finished products. They existed to answer a few key questions: Does the idea work? Does the cast click? Is the tone right? And is this worth investing in further?

Most pilots never aired. Many were screened only internally. Some were tested with limited audiences or advertiser groups. Only a small number moved forward to series.

It wasn’t a perfect system, but it gave television a clear path from idea to air.

Why Pilots Were Expensive—but Still Made Sense

One thing that’s often misunderstood is the cost.

Pilot season was not cheap.

By the 1990s and early 2000s, individual pilots regularly cost millions of dollars, especially scripted dramas and comedies. Sets were built, casts hired, and crews assembled—often for shows that would never go any further. Budgets also included director deals, actor contracts, and the early onboarding of department heads and crew, long before anyone knew whether a series would be ordered.

In some cases, experienced crew members were even pulled from active shows for short periods to staff pilot shoots, temporarily disrupting productions that were already underway.

All of that added up quickly.

But networks didn’t see pilots as wasted money. They saw them as contained risk. Spending a few million dollars on a pilot was far less dangerous than committing to a season of episodes without knowing whether the show worked at all. This system of pilot season television allowed networks to evaluate ideas before committing to larger series orders.

Industry reporting from The Hollywood Reporter and Variety has covered how pilots and network economics shaped broadcast development for decades.

A Firsthand Look at the Scale

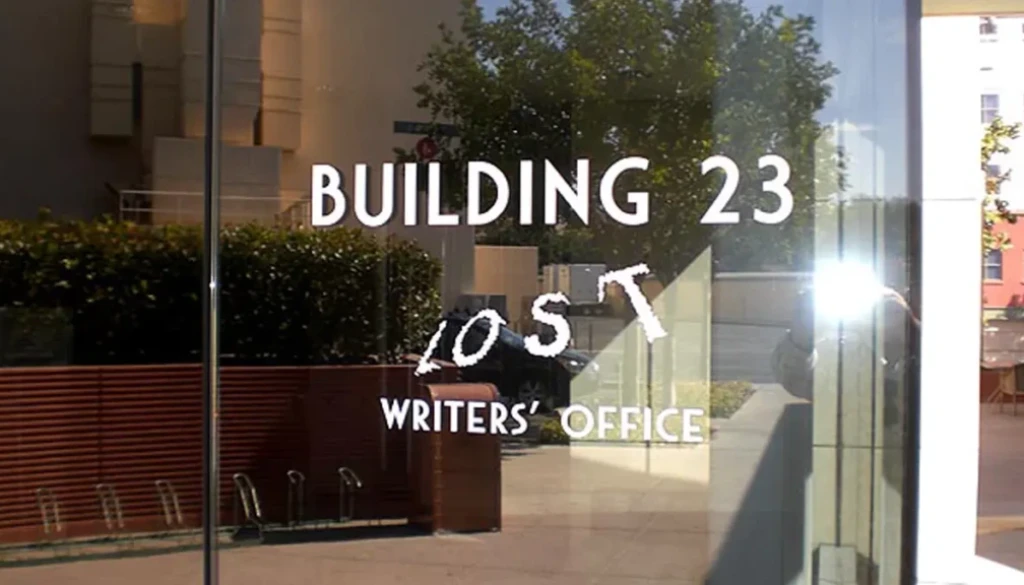

I saw this up close during my first real experience with pilot season in 2004, when I was working at Disney, specifically at Touchstone Television, on the pilot of Lost.

From the start, it was clear the project was large. The scope, ambition, logistics, and cost were on a different level than anything I had worked on before.

Everyone knew the pilot was expensive, and that awareness shaped the atmosphere. The studio and production teams were seasoned professionals, so there wasn’t concern so much as focus. It was clear we were working on something ambitious, and that sense of scale informed how decisions were made.

There was also some irony built into it. The pilot of Lost included a full-scale crashed airplane—not a miniature or a suggestion, but an actual wrecked plane used on set. For a first experience with pilot season, it was a memorable way to learn that pilots weren’t abstract exercises. They were real, expensive commitments made long before anyone knew how audiences would respond.

That experience stuck with me. Pilot season was never casual. It was deliberate, calculated, and very aware of the money involved.

The 13-Episode Model and How Shows Could Disappear Quickly

Another common misconception is that once a show was picked up, it was guaranteed a full season.

It wasn’t.

If a pilot was approved, the network typically ordered an initial 13 episodes. Those episodes were often not completed all at once. Production moved forward while the show aired, giving the network time to evaluate performance.

If a show connected with audiences and advertisers responded, additional episodes—the “back nine”—could be ordered. If it didn’t perform, the show could be pulled from the schedule quickly, sometimes after only a few episodes had aired.

When that happened, production usually finished whatever episodes were already in progress, and then stopped. The remaining episodes in the original order might never be made. Crews were released, sets were struck, and everyone moved on.

It was another layer of risk control built into the system. Nothing beyond what was actively being shot was guaranteed. Understanding pilot season television helps explain why today’s production model feels so different by comparison.

Why Advertisers and Scheduling Mattered So Much

Pilot season also existed because of how broadcast television made its money.

Advertising drove everything. Networks needed to give advertisers confidence in where their dollars were going, and pilots helped do that. They provided a tangible sense of tone, audience, and brand fit before fall schedules were locked in.

The fall lineup anchored the entire broadcast year. It shaped upfront ad sales and determined midseason replacements. Pilot season fed directly into that structure.

Television development wasn’t just about storytelling. It was about timing, scheduling, and confidence.

Why the System Lasted

Pilot season lasted as long as it did because it fit the reality of its time.

There were fewer channels. Viewing habits were more predictable. Audiences watched shows when they aired. Networks needed a way to test ideas before making large commitments, and pilot season provided that framework.

It also allowed room for experimentation. Many shows that later became successful didn’t begin as obvious hits. Pilot season gave ideas space to be tested, adjusted, and sometimes reworked before reaching viewers.

But that system depended on stability—fixed schedules, advertiser-driven revenue, and limited distribution.

When the Cracks Started to Appear

By the late 2000s, that stability was fading.

Cable expanded. DVRs changed how people watched television. Digital platforms introduced on-demand viewing. The rigid broadcast calendar began to feel outdated.

Pilot season didn’t disappear overnight, but the conditions that supported it were clearly shifting.

And then television changed very quickly.

Coming Next: Part 2

In Part 2, I’ll look at how streaming—led by Netflix—upended this system almost overnight. The move away from pilot season wasn’t gradual. It was a rapid shift that reshaped how television approaches risk, development, and sustainability.

If you want to keep reading, here’s Part 2 of this series. (Link will go live when Part 2 is published.)

Related reading: How streaming changed television and the economics of streaming TV.